One of my consolations in this strange and troubling year is discovering the pleasures of translated fiction. My pre-blog reading life (as I’ve noted before) was largely confined to the anglophone world, with a mild tilt towards British authors thanks to my devotion to The Guardian’s book section. Oh, I did read a translated novel here and there over the years, but when I did so it was almost always something from a European country; my two categories were either works that made a huge splash on my side of the Atlantic (Leila Slimani’s The Perfect Nanny and Herman Koch’s The Dinner spring to mind) or one of those big, sprawling 19th century chunksters that so impress one’s colleagues during those stimulating Monday morning conversations around the water cooler. (“Did I happen to mention that I read War and Peace last weekend? Tolstoy has such a penetrating view of history, don’t you think?”) I very rarely read any contemporary fiction in translation and I almost never read anything, contemporary or classical, from a non-European country.

My, how things did change, once I started traveling through the blogosphere! It didn’t take long for me to see the riches I had been missing and to add a great many new titles to my ever expanding TBR mountain (thank you very much, dear Kaggsy, for your excellent recommendations!) And then, there was the fun of discovering new publishers, such as the Pushkin Press, the Fitzcarraldo and the Europa Editions (if any of you dear readers have other publisher recommendations, do please share). After dipping my toe into non-western waters last winter thanks to Dolce Bellezza Japanese Literature Challenge, I decided the time was ripe for a mild exploration of a few more translated works.

And what better time to start my adventure than in August, which is both Spanish literature and Women in Translation (WIT) month? In honor of both occasions, I’ve been having a lot of fun reading several works that fit into either category, with at least two novels (Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dreams and Maria Graina’s The Optic Nerve) that fit both. In addition to the thrill of discovering these new (to me) writers, I’m very much looking forward to reading all the great reviews that are currently popping up on some of my favorite blogs. Hopefully I’ll be sharing a few of my own thoughts on my discoveries in the upcoming weeks as well.

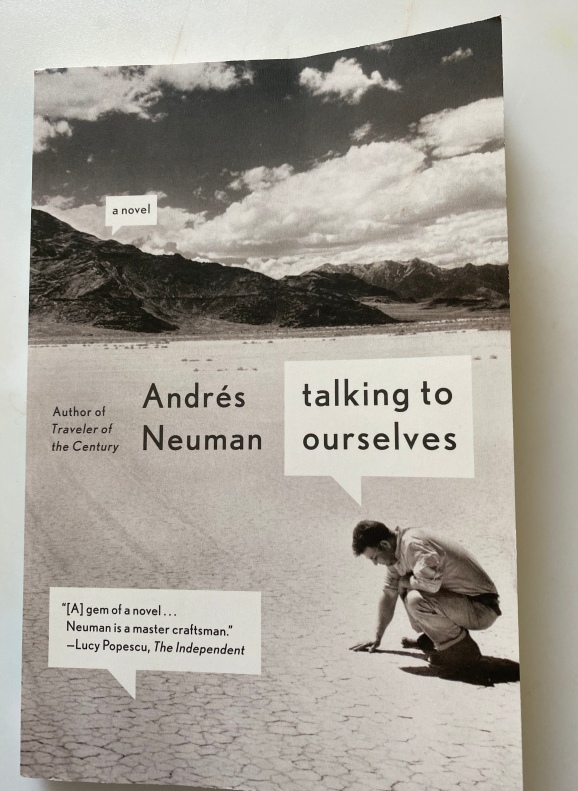

Because I’ve traveled fairly extensively in certain parts of Latin America (but have never, alas, visited Spain), I rather arbitrarily decided to focus on the former area in selecting my translated-from-Spanish novel. I also wanted to read a very contemporary writer who’s currently publishing rather than an established giant of the canon such as Borges, Llosa or Marquez. Earlier this summer I became interested in Andrés Neuman, an Argentinian novelist with strong ties to Spain, when I read a recent Guardian review of Fractures, his latest novel translated into English. In keeping with my general ignorance of international literature, I was amazed to discover just how much Neuman has written (he has over twenty works of fiction and non-fiction under his belt), the wide range of his talent (Neuman is a poet and essayist as well as a novelist) and just how highly he’s regarded by those who should know (Roberto Bolaño, no less, proclaimed that 21st century literature would belong to this guy and as if that wasn’t enough, Granta included him in Volume 113, its selection of the best young Spanish language writers). Despite this renown, however, only three of Neuman’s novels have currently been translated into English. A copy of the earliest of these, The Traveler of the Century, wasn’t readily available to me; between the two that were, I decided to begin with Talking To Ourselves based largely on whim (also, I must confess, I loved the cover photo, despite the insertion of those stupid conversation “balloons”).

Talking to Ourselves is one of those novels whose brevity is disproportionate to its impact. Clocking in at a mere 160 pages or so, it can be finished in an afternoon, but its reverberations continue long after you’ve read the last word. I found myself puzzling for days over various aspects of the story and finding new layers of (possible) meaning in various incidents or characters. I don’t want to suggest that Talking is a difficult read — it isn’t; there isn’t much external action and the number of characters is primarily limited to the eternal triangle of man, woman and child. Rather, like the great artist he is, Neuman works on many levels and leaves it up to to the reader to decide how deeply he or she wants to delve.

The novel opens with a quarrel between Mario and his wife Elena; Mario, it seems, wants to borrow his brother’s truck and take Lito, the couple’s ten year old son, on a road trip to deliver an unspecified cargo to a small, remote town far from the family home in Buenos Aires. Lito is very excited at the propect of this long-promised treat while Elena is very much opposed. We shortly learn that Mario is dying (almost certainly from cancer, although the cause is never specified); when the novel opens his disease is in (temporary) remission and he desperately wants to create a lasting memory for Lito to cherish after his father’s death. Mario and Lito embark on their journey while Elena, who remains behind, commences her own very different odyssey.

Lito, Mario and Elena each tell the unfolding story through his or her point of view (POV). This limited view point not only keeps the reader guessing but also deepens our understanding of certain incidents. Lito, for example, thinks his father reacts rudely to a “magician” they encounter on their road trip; Mario’s puzzling actions become clear later on when he narrates his own section and indicates his opinion that the “magician” is most probably a pedophile who’s hitting on his son. The shifting POV also imparts suspense into what might otherwise be a rather claustrophobic domestic drama by allowing the reader access to information Elena and Mario withhold from each other and from Lito (both parents, for example, lie to their son about the extent and nature of Mario’s illness and death).

Although Mario does the dying (he is, so to speak, the novel’s guest of honor), the novel really belongs to Elena, an academic manqué whose lack of conviction and desire to get married led her to abandon graduate study. Far more intellectual than Mario, Elena attempts to understand her grief by reading and reflecting on great works of literature. We know her thoughts through her journal entries, as we know Mario’s from the recordings he makes (after his death, these will ultimately be given to Lito) and Lito’s through his texts and stream of consciousness narration (it’s a mark of Neuman’s skill that he makes each character communicate in a way that reflects his or her personality). As Elena looks to literature to make sense of herself and her disintegrating world, the novel interweaves her thoughts about what she is reading with actual quotes from the works themselves. As Elena explains:

When a book tells me something I was trying to say, I feel the right to appropriate its words, as if they had once belonged to me and I was taking them back.

“She has already started to wear sunglasses indoors, like a celebrity widow,” I was startled to read in a short story by Lorrie Moore, sometimes I do the same, using my photophobia as an excuse, so that Lito won’t see my eyes. “From where will her own strength come? From some philosophy? From some frigid little philosophy?” Actually, I don’t get my strength from reading, but I do understand my weakness.

Although Neuman overdoes this device a bit, it’s a very interesting stream of consciousness technique that gives a real sense of immediacy to Elena’s reading (the novel contains a bibliography listing the works that Elena cites, which range from César Aira and Margaret Atwood to Hebe Uhart and Justo Navarro).

A major portion of Elena’s journal entries deal with a clandestine affair that begins shortly after Mario and Lito depart on their road trip. Despite feeling increasingly guilty about her actions, Elena responds to her husband’s approaching death by engaging in an intense, very physical affair that has heavy sadomasochistic overtones. As Elena explains (Talking at 44-45) in her journal, the physical and psychological pain she gives, and receives, from this affair resurrects and awakens her; she and her lover (who is experiencing a loss of his own) “cause each other pain in order to make sure we are still here.” I’m less morally repulsed than somewhat unconvinced by Elena’s actions, which strike me as a bit contrived (I found myself thinking that this novel was written by a man, after all, but then perhaps I’m being naive). It’s perhaps significant, perhaps not, that Elena’s lover is the one important character we see only from the outside; he alone has no voice. Although this may simply emphasize his relative unimportance vis-à-vis the bond between Elena and the dying Mario, for me at least his silence and the opacity of his emotions and motives increased my inclination to regard him as a rather artificial plot device.

Unsurprisingly for such a short novel, there’s a dearth of secondary characters. Elena’s parents and older sister, and Mario’s brothers, make brief, fleeting appearances or are referred to in passing. When they do appear, however, Neuman can bring them alive with a line or two. My favorite of these is Elena’s older sister. Never given a proper name, she quarrels with Elena and leaves her house in a huff after she learns of Elena’s affair; polite, dignified and insufferable, she informs Elena of her departure by text message. A subsequent exchange between the sisters conveys the essence of many sibling relationships:

Do you need money? my sister asked in that responsible tone my dad admires so much. No, I pretended, why do you ask? No reason, she replied, how much do you need? When I said the amount I felt odd, grateful, younger.

I’m afraid that my bare summary may leave you with the impression that the novel is melodramatic and emotionally bleak. If so, I’ve done a severe disservice to Neuman’s skill and subtlety. Talking is surprisingly funny in spots, an effect Neuman achieves in part by making Lito the narrator for part of the road trip with his father. I usually become pretty wary when a child protagonist appears, as all too often s/he is either too cute, unrealistically precocious or both. In Lito, however, Neuman finds the realistic (and very funny) balance between the awareness and the innocence of a ten year old, as this exchange between Lito and his father (Talking at 32) makes clear:

I send a text from Dad’s phone:

hi ma hw r u? we r awsm! saw ++s of grt plcs 2day dt worry dad nt drvg fst 🙂 xxxs luv u

Mom replies:

Thank you my darling for your delicious message. Your mom is fine but she misses you loads. Be careful climbing in and out of Pedro [the truck]. I went swimming today. You are my angel, kiss Daddy for me.

Mom doesn’t know how to use the phone, I laugh. What do you mean? Dad says, she uses it every day. And she had one before you were born * * * Sure I say, but she doesn’t know. Her messages always have twenty or thirty letters too many. It’s more expensive. And she wastes about a hundred letters. * * * And you, I go on, don’t know how to use it either. Oh, heck, pardon me, he says, why? Let’s see, I say, where in the menu do you find the games? That’s unfair, he complains. Ask me about something I might have a use for. Okay, okay, I say. How do you copy your contacts list? He doesn’t say anything. You see? I say. Then I raise my arms and whoop like I’ve just scored a goal.

What the reader knows, but Lito does not, is that this will be the only trip the little boy will ever take with his father. With a lesser writer this could be mawkish; with Neuman it’s bittersweet.

A road trip, a family drama, an account of the consolations of literature and of the journey from life to death and from grief to possible healing, Talking to Ourselves is a complex little novel that packs a lot of content into its scant pages. The complexity of the book and the richness of its ideas allow a reader to approach it from many angles; while I’ve chosen in my review to focus on Elena, a different reader might well (and with equal justification) concentrate on Mario. The translation, which seems outstanding to me (admittedly, my knowledge of Spanish is pretty rudimentary) was done by Nick Caistor and Lorenza Garcia, the very talented team who have also translated Neuman’s two other novels into English. Although I admired Talking to Ourselves more than loved it, and had a few reservations here and there, Neuman is a wonderful and subtle writer whose works I’ll continue to explore. If any of you, dear readers, have read Talking or any other of Neuman’s novels, I’d be most interested to hear your opinion of his work (I’m personally wasting no time in clicking over to Tony’s Reading List to see what he has to say about Fractures!).

As I noted at the beginning of this post, I absolutely loved the wonderful cover photo, so much so I tracked down the original image in order to look at it without the distractions of superimposed text. The original photo was taken by Fritz Goro, a refugee from Nazi Germany known primarily as a science photographer. Don’t you think this image has a haunting, mysterious quality?

The image is stunning, and the book itself sounds really interesting (and I am happy to have been a bad influence when it comes to translated books!) I like the idea of the three different narrators gradually revealing things as the book goes on – a very clever device. Interested in your pereception of Elena’s affair – and I don’t think it’s wrong to wonder whether it’s unconvincing because written by a man. I’ve found myself uncomfortable with male portrayals of women characters in the past so it’s a valid consideration!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think Elena’s affair is something that might trouble a lot of readers — not just infidelity, but infidelity while one’s husband is dying. I’m still on the fence about how believable I found it, perhaps because of the lover’s role. I actually found the lover extremely interesting, but kept my comments about him to a minimum because I didn’t want to spoil it for anyone else (I might add there’s not a lot of suspense here, but still . . ); there’s a certain deus ex machina quality to him and also a fair amount of symbolism. Neuman actually does a very skilled job in describing Elena’s reaction to her husband’s physical deterioration, placing her hunger for sheer, healthy physicality in context, a sort of “in the midst of death I am affirming life” kind of thing. Nevertheless, I do get a whiff her of male fantasy (once it’s been sniffed, it’s never forgotten . . )

I do love Elena’s response to life; her first reaction (aside from her affair, that is) is to read, to look to her books for insight. A different review could have (almost) interpreted he entire novel along a “literature as consolation” theme. The depth of Elena’s reading is very impressive (I added a couple of titles here to my own list; the bibliography is quite useful!). It really is amazing how much content this little novel has; I feel quite exhausted and am ready to head over to the Furrowed Middlebrow series right now (just been reading some excellent reviews of Ruth Adam!)

And, yes, you & others have been quite the influence for translated literature — I am really becoming quite an enthusiast, with book shelves that are groaning with the weight of unread volumes . . .

LikeLike

It’s really interesting to see your perspective on this. I read the novella 5 or 6 years ago and recall it feeling very layered, almost like the literary equivalent of a collage with the different voices and textures coming together to make an intriguing portrait. (There’s a short review over at mine if it’s of interest.) In terms of form and style, Neuman’s book reminds me a little of another (much earlier) Latin American novella I read recently, Mario Benedetti’s Who Among Us?, which also featured three very different voices…

LikeLike

Jacqui: so nice of you to stop by, although I’m quite envious of your word choices — I only wish I’d thought of the word “collage”, which actually describes Talking to Ourselves” perfectly! I’d love to read your review but can’t find it — could you send me a link? I did find, and read, your excellent review of Neuman’s “The Things We Don’t Do” and instantly added it to my TBR list (which admittedly has about a million items by now). I take it from your remarks that you’re also a big fan of “Traveller of the Century,” correct? (if you reviewed it, could you send me a link to that as well?). I understand it’s quite different from “Talking to Ourselves” and I’m eager to check it out, as I finally located a copy (the novel has now made it from the TBR list to the TBR shelves). I haven’t read anything by Benedetti, so he’s another author to add to the list (I’m becoming quite interested in Latin American fiction — such an exciting area!)

LikeLike

I can see myself in what you describe at the beginning of your post; before 2006 I had not read much translated literature at all (short of what was popular like The Dinner, or House of Spirits, or Like Water for Chocolate).;) Of course, I had not really known of Japanese authors either, hence my exploration into them for my blog. It all sprang from my love for origami, which I used extensively in my elementary classroom as I taught. At any rate, isn’t discovering translated lit the richest of experiences?!

Your post on Andres Neuman reminds me I have long meant to read a Traveler of the Century, which I bought one year for $1.00 from our library which wouldn’t know a good book if it landed on their shelves. “We have to appease the masses,” they tell me, when I inquire why they lack so much literature in translation.

But, I digress. I’m so glad you joined in the Japanese Literature Challenge, and now you’re finding these wonderful gems to be had. I am in such a discovery myself. xo

LikeLike

Bellezza: so difficult to believe that you weren’t always a read of translations, as your blog is one of my “go to” places for translated literature! Even though I didn’t participate as actively as I wanted to last winter (I was in the middle of a long distance move, stressed and packing many, many boxes), your Japanese literature challenge really provided a massive incentive for me to break out of my self-imposed limits. I totally agree with you that the discovery of translated literature is, indeed, one of the richest of experiences and — I’m just getting started!

Somewhere between reading Talking to Ourselves and actually writing the post on it, my copy of Traveler of the Century finally arrived. I’m very, very behind in writing blog posts (I’m an extremely slow writer) so it will probably be some time before I get to it, but Neuman is now definitely on my radar.

I loved your comment about your library — back in the (student) day, I worked in both a public and academic library as a very low ranking little worker bee (I actually have a degree in library science, which I never really used). Although I thoroughly enjoyed the experience, it could be just a teeny bit depressing to see some of the selections offered, and choices made. If worthwhile books aren’t offered to folks, well, they aren’t going to be checked out and read, are they? I view a library’s role as more of a light beacon (which illuminates bookish treasure) than a mirror (to popular taste), if that makes any sense. Of couse, there always have to be compromises but still . .

Although I haven’t finished any works of Japanese fiction recently, I recently acquired Kawabata’s The Old Capital & Tanizaki’s The Maids, both of which look very promising. I’m also about half way through Riku Onda’s The Aosawa Murders, which I thought would be a nice break after a few of my Latin American reads. So far, it’s great, if you’ve a taste for that genre.

LikeLike

I love this passage in your comment: “ If worthwhile books aren’t offered to folks, well, they aren’t going to be checked out and read, are they? I view a library’s role as more of a light beacon (which illuminates bookish treasure) than a mirror (to popular taste), if that makes any sense. Of couse, there always have to be compromises but still . .” wonderfully said!!

We will have to talk about the Aosawa Murders when you finish. I liked it very much, but felt there was more going on between the mother and daughter than was readily apparent. That was the real mystery to me.

Such fun to talk books with you! I don’t think you must be a slow writer; I think you are a thorough and thoughtful one.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ohhhhh, you’ve read the Aosawa Murders! It will be fun to compare notes when I finish. I was thinking that I might post about it for WIT month, if I get around to writing it up.

I love talking books, which is what drew me to blogging in the first place. If you’re ever in the mood for a nice natter that doesn’t fit into the blog post/comment format, please don’t hesitate to contact me (I believe my blog is set up for email).

Public libraries are interesting places, aren’t they? There’s no better place to see a community’s values and standards (or lack thereof) in action. It’s been ages since I worked in one, or studied how to work in one, and in the meantime the field has totally changed. I always found it sad to see what treasures were discarded at the annual book sales (on a positive note, they went to readers who valued them) or, more likely, never ordered.

Thank you so much for the lovely comment about the writing, but — I AM slow, which is why I don’t post that much. I’m trying now to work up the energy to review Nella Larsen’s Quicksand, which I read last June for the Back to the Classics Challenge. It’s a fascinating read, although perhaps not quite up to Passing, her other work.

I forgot to add in my last comment that I’m in awe of ANYONE who can do origami. It’s such a lovely art form. The reference to it in the Aosawa Murders revived my interest in it, as I had no idea really that it had such a long, rich history. When I read the detective’s section, I remember making a note to check out my hunch that the connected cranes origami piece might be a clue!

LikeLike

If I may expose myself at my worst. I don’t like any Spanish culture: I don’t like the food, the art, the music and especially the literature. I don’t like the sound of the language, that they don’t get up in the morning and eat breakfast, that you have to eat dinner at 11pm. I don’t even like Almodovar’s movies and I have a big tolerance for film. May I never hear another guitar.

But a while back I read John Berger on Goya and it really made me think that I have to try harder. So I constantly read posts like this one searching for clues which will get me over my antipathy 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

Greetings CathyC! I think it’s great that, despite your present dislike, you’re keeping an open mind and are continuing to investigate a subject & culture that has little appeal for you at this precise moment in your life. One thing that I’ve found very odd and delightful about my own journeys in this regard is just how radically my opinion on various subjects has changed (at least sometimes) as I spent energy & time exploring them. Translated literature, for example — as I noted at the beginning of my post, it simply was not my thing. In fact, I absolutely refused for many, many years to read pretty much anything not originally written in English. Now I’m in the beginning of a new, full blown enthusiasm; I know this because I’ve gone through a similar process with many other things: opera (most boring music in the world but I’ll listen to it for a year just to make sure; two years later, I almost went broke buying opera tx); Baroque art (fat ladies on pink clouds; now I’m a (relatively restrained) Rubens fan not to mention Titian & Rembrandt; Vermeer is still a struggle); Henry James (wrote a post on this one) & George Eliot (started reading her at night to put me asleep. After three months ithis didn’t work and I now think Middlemarch is one of the greatest novels ever). Sometimes, of course, the process has the opposite effect: I will never be a baseball fan (believe me, Mr. Janakay has really, really tried to convert me) or, like you, be a big enthusiast of guitar music. I think you have the gist of it down, however — investigate until you’re absolutely sure of your opinion, especially if it’s negative.

On a different note — isn’t John Berger great? Such a brilliant thinker. I’ve only read a little by him and that’s my loss; I really hope to read more. As for Goya — his paintings are stunning, n’est-ce pas, especially the dark ones. Your comment is reminding me that it’s been a long time since I looked at any images from Los caprichos.

Anyway, keep investigating away. Who knows? the next time we exchange views (I always find yours very stimulating BTW as they make me re-think my own) I’ll be reading books about social platforms and you’ll be on your second re-reading of Don Quixote! : )

LikeLike

Don Quixote, case in point – I didn’t even want to see the recent movie.

I’ve never felt bad about reading translated literature, but on the odd occasion where I compare two translations it makes me reluctantly accept that it’s a case of the best of a bad business. Most recently I read Lost Illusions by Balzac in translation, wanted to put a couple of pages of it on my blog, went to the nearest online translation and realised whilst reading it how inferior it was….but that was in the part I was reading at that moment. Somewhere else it was better than the one I had in hand. Yet even in full knowledge of the deficiencies of a translation, I dearly love much of what I’ve read that way and my reading life would be vastly the poorer for not having done reading translated works. The arguments I’ve had with my partner about this, since he reads only in the original, and has several languages he can read at a high level.

LikeLike

Cathy: the point you make about translations is a good one. In fact, that and the realization that I was reading the translator’s approximation/version of the original work were largely what kept me away from translations. I envy your partner — if I could read in the original I would — but failing that, it’s translations or nothing for a chunk of the world’s literature. Even with all the deficiencies/drawbacks, translations are enormously enriching, an realization you seem to have come to much sooner than I. I think I’m so excited now by what I’m reading because I feel that my world is expanding exponentially; that just as I thought I knew the terrain pretty well — voila! another new continent(s)! (please forgive the hyperbole — it’s early morning here and I’m not yet fully aware).

On a different subject: I forgot to ask if you’ve read/heard of Isabel Wilkerson’s newly published book “Caste: the Origins of Our Discontent,” an examination of the underpinings of race treatment in America. It’s getting a strongly positive reaction and sounds fascinating. https://www.npr.org/2020/08/04/898574852/its-more-than-racism-isabel-wilkerson-explains-america-s-caste-system. I have not read Wilkerson’s previous and highly regarded “Warmth of Other Suns” (the story of the great migration south to north) despite having a copy for many years (if you’re interested in visual art, particularly art with a social/historical edge, Jacob Lawrence’s “The Migration” series is fabulous. https://lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org/the-migration-series). Nevertheless, I’m putting Caste on my list although I read non-fiction so slowly it will probably take me years to get around to it.

LikeLike

Based on my understanding of caste as it exists in India, I find it hard to interpret US society/economy through it and the report you link to hasn’t helped. My sense of caste is that it’s there to make people different who aren’t. Ie, one can’t just point to the colour of their skin or their language and make distinctions. I also thought it is all about however miserable your lot is, knowing that there is somebody worse off. Yes, you have a group at the very bottom who can’t look on this ‘bright’ side, but most people can. Maybe I just don’t get ‘caste’ but if I do, then does this really explain the US? Then again, maybe I don’t really understand the US either.

LikeLike

Hi Cathy: I mentioned Wilkerson because (based on our previous exchanges) it seemed that you had an interest in U.S. social issues and her book is getting a LOT of buzz (I’d expect it to be nominated for the Putlitzer or some such). I’m sorry the link wasn’t helpful to you; I sent you the quickest I could find, with the idea that it could give you some minimal info if you wanted to go further. The review in the NY Times might be more helpful:https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/04/books/review/caste-isabel-wilkerson.html

At any event, there’s lots out there about it.

I don’t speak with any particular insight here, but I think that the basic idea is that caste is something you can’t change while class is something that you can. One is born into a caste and one stays there, regardless of one’s accomplishments. Class, on the other hand, can be more fluid and its indicia (education, dress, accent, material possessions and so) can be adjusted or acquired. My own family, like many, were coal miners and share croppers; later on (after minimal industrialization moved into the region because of cheap labor) you can add textile workers. Luck and free public education made it possible in the 20th century for us to become something else — our caste (white) stayed the same, class maybe shifted. One of my African American colleagues, who came from the same region, began life on a much higher class level — his family owned land, in contrast to mine, and were prosperous farmers. My colleague and I had very comparable educations and career paths (his was a bit more successful). Under a caste view of things, his accomplishments, however, meant nothing, because his caste didn’t change; it remained African American. The “one drop” rule that prevailed in the south, i.e., one teeny little bit of non-white DNA meant that one wasn’t white, served to reinforce all this. Anyway, that’s how I (perhaps incorrectly) understand Wilkerson. She also discusses the idea of caste as it was practiced in Nazi Germany vis a vis its Jewish population. I haven’t read her book however (I do have a copy) so perhaps I’ve muddled all this!

LikeLike

Thank you Janakay, your own experience explains this much better to me. Very depressing to think it is that bad in the US. I should read the book!

LikeLike

Cathy: I think it might be good for us to re-visit this conversation after we’ve BOTH read the book! (I believe my site is setup for email, so feel free to contact me if your comments don’t fit into my posts). The U.S. is a big, beautiful, diverse country (I loved the fact that, until my move last spring, I was living close to the largest Ethiopian community outside Addis Ababa and that metro notices in my area were printed in over 40 languages); like most polities with such racial & ethnic diversity, well, there are problems and injustices, sometimes murderous ones. But I’m actually quite proud of the fact that there’s a real movement to understand these problems (Wilkerson’s book, for example; there’s a raft of new civil war & reconstruction scholarship; lots of wonderful literature by writers of color and — well, I digress). Wilkerson, as I understand it, is describing the origins of the U.S.’s racial structure (could be wrong here); please consider that times have changed although, of course, the debate about how much is endless (you might be interested to know that my African American colleague was much more optmistic than I when we compared notes about our mutual southern heritage). The apartheid system of my childhood & youth is in history’s dustbin (where it belongs); non-white minorities are advancing politically & economically (Barrack Obama anyone? Kamala Harris’ nomination); Mississippi ditched the confederate battle symbol from its state flag and the list is endless. Peaceful and perfect? no, but . . . unlike the situation in many societies, the problems’ are being acknowledged & analyzed and attempts made to grapple with them. I guess we’ll have to wait to see history’s verdict on the outcome.

I try to remember the great quote used by Dr. King, to the effect that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice. Of course, we do have to help the arc along and not rely upon it to bend itself, so to speak! And, since I’m in a quoting mood, the very Preamble to the Constitution states that, “in order to form a more perfect union” implying, of course, that the American experience is that of flawed human beings striving to do better. Obama, of course, recently expressed this in a matchless way in his eulogy of the late and very great John Lewis. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/07/read-barack-obamas-eulogy-for-john-lewis-full-text/614761/

LikeLike

Yes, Janakay, this conversation will definitely have to be continued later.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful post, Janakay. I’m ignorant of any contemporary or even XX century literature in my language, be that Spanish or Latin American. It’s such a vast range, like literature in English. This book and author have caught my attention. I enjoyed your review. I also appreciate well rendered children in literature. This is something I admire in Galdós, one of the best writer of children and teens I’ve ever read. Though there may be many who nail this and I don’t know about, LOL. When I read this book I’ll let you know about the affair, if it also feels a bit contrived. I see how the book is powerful, because look at the review, and just 160 pages.

After this comment, I’m going to read your interesting conversation here on the comments. I love the discussion, you all bring so many interesting points of view, and the talk on translation is always so rich. I acknowledge the different views. I may be optimistic because I, like Janakay, have no option but to read in translation many authors I want to read, specially Japanese and Russian, and other languages besides English and Spanish. I may be strange, but even some English works I’ve read and loved in Spanish. It may depend on the book, and on our personalities, expectations, views of what we miss versus what we gain.

However, translation is not everybody’s cup of tea, and I get that.

And the image, it instantly enamored me as well, best like that, without the cover speech bubbles, is arresting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just stopping in to say “HI”! The internet and the 21st century have also opened up a world of translated literature to my attention. I have to admit that I rely on the Tournament of Books annual competition, however, to make me read much of it. I read both Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dreams and Maria Graina’s The Optic Nerve because they were on the short list (Fever Dreams actually won the TOB in 2018 and Optic Nerve came close to winning this year). I would particularly be interested in your opinion on Optic Nerve because of the art angle. Did it work for you? I have to tell you now, neither book lit a fire for me, but I did enjoy reading them.

Talking to Ourselves sounds very much like something I would like. I am in awe of those short books that really pack a punch. It is like some sort of alchemy…how do they do it when other authors use so many works and still aren’t as successful?

LikeLike

Ruthiella: I’ve missed you! So delightful you dropped by, particularly as I’ve frequently had problems accessing your blog (I can usually read it, but often can’t leave comments). For the moment, Firefox seems to be doing the job, however. I very much enjoyed your discussion of The Dud Avocado.

I really must check out the Tournament of Books next year, as it sounds both fun and enlightening. The reviews on various blogs and the monthly events, such as WIT and Spanish Lit, have really propelled me into translated fiction. I find it particularly exciting because, quite honestly, I was becoming a bit jaded with my reading choices. It’s exhilarating to discover that even now there’s a whole new area yet to explore.

I am, alas, very lazy about reviewing my selections, having several at this point in the queue, so to speak, including Fever Dreams and Optic Nerve. I thought Fever Dreams very aptly named — a nightmarish rollercoaster of a novel (well really, a novela) that made sense in that weird, surrealist way of a really creepy dream. I’m still not sure I figured out the “plot,” or, indeed, whether there was one. I found it more of a mood, really, than a traditional novel, almost like a prose poem. As for Optic Nerve — on this matter, dear friend, we definitely part ways! It was one of my major reads of the year, right up there with Warner’s The Corner That Held Them. I loved everything about it, from the fragmented story line, the poetic style and, yes, the art angle. Don’t you think it was really more a collection of short stories than a novel? At the very least, the plot was certainly non-linear; I could imagine re-reading it in reverse order and not losing anything at all. Is Graina telling us that our identities are mere reflections of our sensory inputs; that identity is formed by how we experience art; that we don’t really HAVE an identity to speak of (remember the section where she literally sees herself as a child in a particular painting — can’t remember the artist) or has she just found a clever way to tell a story? I’ve been thinking about that book quite a bit. In fact, I was really trying to work up the energy to review it this weekend before the end of WIT month, but decided to visit one of the few museums that is open right now to experience some art myself, albeit in a far less complicated way. So much more fun than writing, which I don’t really like to do much.

I think you might like Talking, as you said, it packs quite a punch for such a short work. If you get around to reading it I’d be interested to hear your thoughts (if you’d like my copy, send me an email–I think my blog is set up for this–and I’ll be happy to pass mine along). I now have a copy of Neuman’s Traveler of the Century, which is supposed to be very different but equally good. It will probably take me a decade or two to get around to it, but we’ll see.

What are you reading these days? I’m in one of those “in between” states where nothing quite pleases . . . I’m working on O’Hara’s Appointment in Samara, which is a bit of a departure from my usual and have put away several Furrowed Middlebrow novels. The latter go down like candy and are most soothing, which I can use in these days of plague and turmoil . . .

LikeLike

I agree that Optic Nerve isn’t really a novel in the traditional sense – it was more a collection of autobiographical essays. And for sure one could read the chapters in any order. I typically, however, need a plot to hang on to – otherwise I forget everything. There are exceptions, but I am not sure Optic Nerve will be one of them. I did look up all the artists on the internet while reading, which was kind of a fun, interactive aspect of reading it. I agree that her aim was to show how our interpretation of art of is a reflection of ourselves. I used this quote in my Goodreads review, which I thought sort of summed up her thesis, “I felt like running to the little girl in the picture and throwing my arms around her. I know, I know, this is about as far from hard-nosed criticism as you can get, but isn’t all artwork-or all decent art-a mirror? Might a great painting not even reformulate the question what is it about to what I am about? Isn’t theory also in some sense always autobiography?”

Fever Dream felt to me like a horror novel and was apparently inspired by the use of pesticides in Argentinean agriculture which has caused, or is thought to have caused many birth defects in some local communities. I read someplace that Schweblin said most Argentinians would have made that connection in reading the novel. I also know that some people who are parents had a very strong connection to the story and knew exactly what a “rescue distance” was, even if they hadn’t ever quite articulated the concept to themselves before.

You don’t have to send me your copy of Talking to Ourselves. I’ll buy it and throw a little more money in the way of the publisher to let them know there is an interest in translating more from this author, you know?

I’ve not read any Furrowed Middlebrow books yet but I want to and I want to start with Tom Tiddler’s Ground since I’ve heard such great things. I am trying, however, to read THREE books that I already own for every book that comes in (not counting library books) – so I need to read a little more before I can allow myself to bring new stuff in. So far, my discipline is holding. 😀

I read Appointment in Samara a few years ago. It is kind of a frustrating story and I don’t think I much liked it, but then with the title – I guess his point was that one cannot outrun one’s fate.

I’m reading a bunch of things at the moment. I’ve been working on The Magic Mountain since May – in German – which is why it is taking me so long to climb it. I started William Boyd’s The Ice Cream War which seems great so far (it is a book I own – yippee) but my library hold for the new Murderbot novel, Network Effect, just came in so I need to prioritize that. And I am just about to finish the first book in Durell’s Alexandria Quartet which I kind of hate. But it is supposed to be genius, so what do I know? LOL.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ruthiella: it’s taken me so long to reply you’ve probably forgotten you left this comment! Please forgive–I wanted to think about some of the points you made, wandered off & got distracted and . . . . well, you know! I’m afraid I’ve been semi-out of my blog lately; while I’m reading away I don’t really feel like reviewing the books.

I do agree with you that “Fever Dream” can very legitimately be viewed as a horror novel–in fact, in one sense it’s a long primordial scream. It’s also sort of sci-fi like as well, don’t you think, especially the environmental aspects? Makes you realize how thin the line between genres can be. I tend more towards viewing it as a horror novel, however, because it did have that echo of folk magic, i.e., the thing about transferring part of the child’s soul to another. Anyway, I did find the novel pretty compelling and I’ll place this writer on my “may read more of her work” list.

Re Optic Nerve: I think we’ve had this “plot vs. atmosphere” character discussion before! I agree with you that the novel really had no plot, in a conventional sense; it was much closer to those collections of short stories having having related characters (Olive Kitteridge? perhaps an Alice Monroe work?) than to a conventional novel. That I’m not terribly demanding in the way of plot, and am intensely interested in art history no doubt explains our somewhat different reactions. I love your comment that Optic Nerve had an interactive aspect, as I did exactly what you did, i.e., looked up all the artist as I went along (I actually learned quite a lot). I found the art/identity relationship in the novel pretty slippery; there were times (especially the section where María is convinced the painting of a child IS herself) where Gainza seems to suggest that we ARE what we view. Anyway, I’m getting metaphysical here and, as is painfully obvious, I’m afraid I’ve never been good with this slippery theory stuff.

I’m in awe of your ability to read “Magic Mountain” in GERMAN (triple exclamation points here). I had just enough German in college to know what an accomplishment this is. I’m eager to hear your response to it. Boyd’s “Ice Cream War” is something that I’ve been interested in, but never enough to actually read it. As for Durell’s “Justine” . . . . well….. remember plot vs. atmosphere? It’s very heavy on the latter, which is probably why I loved it. Also, as the Quartet proceeds, you DO get different views/perspectives on events, a sort of Rashomon effect, which I found fascinating. Also, it introduced me to C.P. Cavafy, “the poet of the city,” who turned out to be one of my favs (don’t tell anyone, but when I first read Justine back in my 20s, I thought Cavafy was a fictional creation! Found out on my second read that he was real! What can I say, except we weren’t big on foreign poets in my neck of the woods?) I think you’re in good company in doubting Durrell’s genius; while there are many fans I think that Durrell’s literary rep is in a bit of an eclipse these days.

Appointment in Samara? I’m glad I read it (it’s been on the list for quite awhile) but I’m not sure it belongs among the century’s greatest. It struck me as one of those books that’s valuable for reflecting its era rather than for its literary merit, exactly. I won’t rush out to read other O’Hara novels, although I may well check out some short stories. Eventually.

I enjoyed my Furrowed Middlebrow reads but must admit that by the time I reached No. 4 I was beginning to flag a bit. They ARE fun, however, and I’ll have to check out Tom Tiddler’s Ground when next I’m in the mood.

I haven’t read any Murderbot novels yet, although I’ve seen reviews. I did just finish “The Space Between Worlds,” which I thought almost lived up to the hype. It had a very ingenious idea, good world building/atmosphere and was quite well written. It also had lots and lots of plot, which tired me a bit, but would be quite up your alley, dear Ruthiella!

Well, must pop off to have an hour or two with my classic de jour, Emily Eden’s “The Semi-Detached House.” I’m finding it surprising easy to read, quite frothy, good dialogue and fairly witty. Every 19th century woman novelist is another Jane Austen (some 20th century as well — Barbara Pym springs to me) but Eden really does seem, at least so far, a sort of Jane Austen “lite.” Hopefully this will continue and, who knows, I may even get around to reviewing the book!

LikeLike

Reviews such as this scare me, only because I know there is probably so much excellent literature in translation that I haven’t even heard of, how on earth am I ever going to find the time to read it??? 😳 I’m kind of kidding, but not really. It seems from your review that thoughts from the book are still percolating, which is what good literature is supposed to do. I often feel that if we close a book with a final verdict, the book hasn’t done what it should.

I must admit I’m having trouble keeping up with monthly bookish celebrations, so it’s nice to see others who are in the mix and tempting me with their participation and reviews. While I do read literature in translation (Russian, Greek, French, Latin), I rarely read anything contemporary so it’s encouraging to know there are some good works around. Enjoyed your review and thoughts very much! Take care!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cleo: thanks for the kind words and so glad you enjoyed the review. Like you, I often feel totally overwhelmed with the wealth of great reading choices; so much so that at times I become a little paralyzed! How can I devote time to this particular book, when it means that I’m passing up several others? And that’s BEFORE adding translated literature into the mix or the time/effort it takes to review, which for me is considerable (I’m a slow writer). Although I enjoy contemporary work very much, it is a bit of a gamble; unlike reading the classics you may be spending time on work that actually isn’t very meaningful in any substantive or stylistic sense (at that point, I usually think, “why didn’t I go for an Austen re-read!”).

This is the first year I’ve actually tried to do any type of monthly bookish celebration (love your phrase BTW) and I must admit it didn’t go all that well. I did manage to review this one novel, but there were a few others I never got around to writing about and then, right in the middle of the month, I sort of threw the whole thing over to read a few Furrowed Middlebrow novels to relax! The best laid plans, right?

LikeLike